10 Timeless Pricing Strategies to Increase Sales

Pricing strategy can be challenging, complex, and offers no shortcuts. This reality makes “winging it” an enticing option when you don’t know where to begin.

But that’s the wrong move to make; smart pricing is deliberate. While intuition plays a role and you’ll learn more from getting your hands dirty than armchair analysis, it can be helpful to review findings on pricing that have stood the test of time.

Try the customer support platform your team and customers will love

Teams using Help Scout are set up in minutes, twice as productive, and save up to 80% in annual support costs. Start a free trial to see what it can do for you.

Try for free

10 research-backed pricing strategies

In that spirit, let’s take a look at 10 enduring pricing strategies based on the science of consumer behavior to provide inspiration and insight on how to effectively set your prices.

1. When Similarity Costs Sales

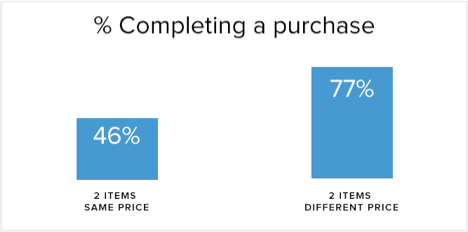

Limiting choices helps combat “analysis paralysis,” as too many options can be demotivating. You might expect, then, that having identical price points for multiple products would be ideal, right? Not always, according to research from Yale: if two similar items are priced the same, consumers are often less likely to buy one than if their prices are even slightly different.

In one experiment, researchers gave users a choice of buying a pack of gum or keeping the money. When given a choice between two packs of gum, only 46% made a purchase when both were priced at 63 cents. Conversely, when the packs of gum were differently priced—at 62 cents and 64 cents—more than 77% of consumers chose to buy a pack. That’s quite an increase over the first group.

The implication isn't to set your identical vintage T-shirts at variable prices. Rather, recognize the why behind the inertia: when similar items have the same price, consumers are inclined to defer their decision instead of taking action.

2. Price Anchoring

As the saying goes, the best way to sell a $2,000 watch is to put it right next to a $10,000 watch. But why? The culprit is a common cognitive bias called anchoring. Anchoring refers to the tendency to heavily rely on the first piece of information offered when making decisions.

In a study evaluating the effects of price anchors, researchers asked subjects to estimate the worth of a sample home. They provided pamphlets that included information about the surrounding houses; some had normal prices and others had artificially inflated prices. Both a group of undergraduate students and a selection of real-estate experts were swayed by the pamphlets with the higher prices. Anchoring even influenced the professionals!

Placing premium products and services near standard options may help create a clearer sense of value for potential customers, who will view the less expensive options as a bargain in comparison.

3. Weber's Law

According to a principle known as Weber’s law, the just noticeable difference between two stimuli is directly proportional to the magnitude of the stimuli. In other words, a change in something is affected by how big that something was beforehand. Weber’s law is often applied to marketing, particularly to price increases for products and services. When it comes to price hikes, there is no magic number, but Weber's law shows that approximately 10 percent is the average point where customers are stirred to respond. As always, many variables have an effect on pricing. Weber’s law serves as a testing threshold rather than as an ironclad rule.

4. Reducing Pain Points

The human brain is wired to “spend ’til it hurts,” according to the field of neuroeconomics. The limit is reached when perceived pain is greater than perceived gain. Research from Carnegie Mellon University analyzed a number of ways to reduce these pain points and, in turn, increase post-purchase satisfaction and retention.

Here are a few select methods:

Reframe the product’s value. It’s easier to evaluate how much you’re getting out of an $84/month subscription than a $1,000/year subscription, even though they average out to around the same cost.

Bundle items purchased in tandem. Professor George Lowenstein notes that the LX version of car packages is a great example of successful bundling. It’s easier to justify a single upgrade than it is to consider purchasing the heated leather seats, navigation, and roadside assistance individually.

Appeal to utility or pleasure. For conservative spenders, a message focusing on utility is more effective: "This back massage can ease back pain." More liberal spenders were persuaded by a focus on pleasure: "This back massage will help you relax."

It’s either free or it isn’t. “Free” is a powerful word, as demonstrated in Dan Ariely’s book Predictably Irrational. In the example, Amazon’s sales in France were drastically lower than all other European countries. The problem was that French orders had a 20-cent shipping charge tacked on (versus free shipping elsewhere). Pricing well means extracting maximum value, but nickel-and-diming can cause more resistance in the long run.

Sweat the small stuff. In another CMU study, trial rates for a DVD subscription increased by 20 percent when the messaging was changed from “a $5 fee” to “a small $5 fee,” revealing that the devil sometimes is in the copy details.

5. Challenging a Timeless Tradition

Ending prices with the number nine is one of the oldest methods in the book, but does it actually work? The answer is a resounding yes, according to research from the journal Quantitative Marketing and Economics. Prices ending in nine were able to outsell even lower prices for the same product.

The study compared women’s clothing priced at $35 versus $39 and found that the prices ending in nine outperformed the lower prices by an average of 24%.

Sale prices—“Was $60, now only $45!”—were able to beat out the number nine. But when the number nine was included with a slashed sales price, it again outperformed lower price points.

For example, consumers were given the following option:

Was $60, now only $45!

Was $60, now only $49!

The sale price ending in nine outsold the one ending in five, even though it was more expensive. Apparently, pricing with nines may be an old trick, but it’s still effective.

6. Time Spent vs. Money Saved

Why would a bargain beer company like Miller Lite choose “It’s Miller Time!” for its slogan? Shouldn’t they emphasize their lower prices? Stanford University’s Jennifer Aaker argues that in many product categories, customers recall more positive memories when asked to remember time spent with the product over the money saved.

“Because a person’s experience with a product tends to foster feelings of personal connection with it, referring to time typically leads to more favorable attitudes—and to more purchases,” Aaker says. In a discussion published by the Wharton Business School, Aaker notes that many purchases tend to fall in either the “experiential” or “material” categories. Purchases like concert tickets benefit more from “time spent” messaging, whereas designer jean sales are aided by reminders of money and prestige.

7. Comparing Prices

When done poorly, chest-thumping about low prices can grant you a one-way ticket to low sales. According to research from Stanford, the act of comparative pricing can cause unintended effects if there is no context for why prices should be compared. Asking customers to make explicit comparisons about the price of your product and a competitor’s can cause people to lose trust in your messaging. The lead researcher noted, “The mere fact that we had asked them to make a comparison caused them to fear that they were being tricked in some way.”

8. The Power of Context

Is there ever a time when one Budweiser is worth more than another? Logic would dictate no, but bar hoppers know this just isn’t the case. Where you buy affects how much you spend. Economist Richard Thaler put this to the test years ago, and found that customers were willing to pay higher prices for a Budweiser if they knew it was coming from an upscale hotel versus a run-down grocery store. Thaler asserts that context was the simple explanation here: the perceived prestige of the upscale hotel allowed it to get away with charging higher prices.

This is why people will pay more for a “multimedia course” over an eBook, even if the information offered is exactly the same. Perception goes a long way toward justifying whether or not a price is reasonable, so it’s beneficial to create a compelling narrative around a product. Head-slappingly obvious, yet so often forgotten by founders who neglect to position their products.

9. Different Levels of Pricing

Most of us are clueless about the concept of “value,” says professor William Poundstone, author of Priceless: The Myth of Fair Value. As such, we can be swayed in ways we wouldn’t believe possible. Poundstone discusses a study around the purchasing patterns of consumers over a selection of beer (yes, yet another study about beer!). In the first test, there were only two options available: a regular option and a premium option.

(Images courtesy of Nathan Barry)

Test #1

Four out of five people chose the more popular premium option. Could adding a third item and price point increase revenue by targeting those looking for a cheaper option? The researchers tested this by adding a $1.60 beer to the menu.

Test #2

Oops. The cheap beer was ignored and it upended the ratio of standard to premium purchases. This was clearly the wrong choice, since anchoring was playing a negative role. If customers don’t want a cheaper beer, perhaps a more expensive beer might work?

Test #3

Much better. These examples show just how important it is to test out different pricing brackets, especially if you believe you may be undercharging. Some customers are always going to want the most expensive option. That doesn't make an enterprise plan right for every product, but it serves as a compelling reminder that you can almost always find a proper reason to Charge More™.

10. Keeping Prices Simple

In a paper published in the Journal of Consumer Psychology, researchers found that prices that contained more syllables seemed drastically higher to consumers. Odd, right?

Here are the pricing structures that were tested:

$1,499.00

$1,499

$1499

The top two prices seemed far higher than the third price. This effect occurs because of the way one would say the numbers out loud: “One thousand four hundred and ninety-nine,” versus “fourteen ninety-nine.” This effect even occurs when the number is evaluated internally, or not spoken aloud. As silly as it may seem, the implication is similar to editing prose—avoid all unnecessary additions, and prefer the simplest style possible.

Get smart with your pricing strategy

Great products and services are priced on purpose. They have prices that develop over time and are guided by debate, scrutiny, and, most importantly, feedback from paying customers. That’s certainly what we’re striving for with Help Scout’s pricing.

As with all looks at academic research, it’s easy to fall into the shallow trap of “The Science of Science, Backed by Science.” Instead, view research as another company’s case study: a fair jumping-off point for inspiration, but nowhere near the finish line.

The Supportive Weekly: A newsletter for people who want to deliver exceptional customer service.